When did the housing crisis explode in Australia? ABC financial journalist Alan Kohler can trace it back to one year in particular — here's what happened. Reference; ABC News In-depth on Youtube. Australia's Housing Crisis: Market Distortions and the Path to Reform Introduction Home ownership has long been a pillar of prosperity in Australia, but skyrocketing house prices are now threatening this tradition.

Australia's Housing Crisis: Market Distortions and the Path to Reform

Introduction

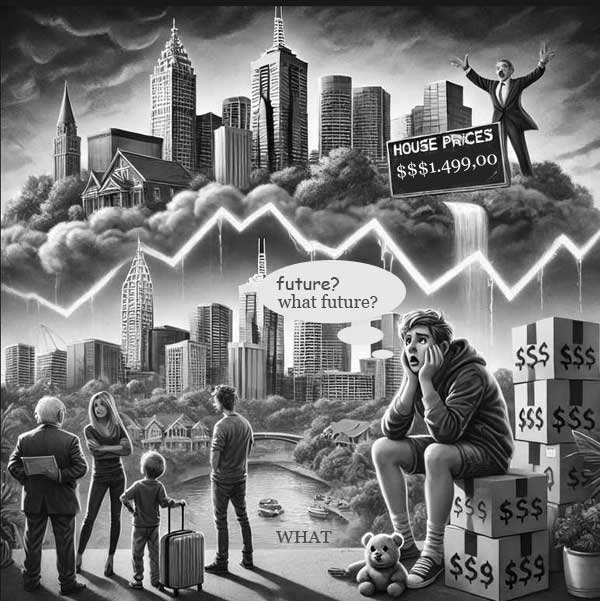

Home ownership has long been a pillar of prosperity in Australia, but skyrocketing house prices are now threatening this tradition. Financial journalist Alan Kohler argues that these price surges have created a societal crisis that requires urgent policy intervention. Speaking at the Sydney Writers’ Festival in partnership with UNSW Sydney, Kohler highlighted how 25 years of market distortions have fundamentally altered wealth creation, pushing home ownership out of reach for many Australians.

The Roots of the Crisis

According to Kohler, Australia’s housing affordability crisis can be traced back to 2000, when house prices started rising significantly faster than both incomes and GDP. This shift was largely driven by policy changes, such as the introduction of the capital gains tax discount in 1999 and the continuation of negative gearing, which incentivised property investment. As a result, investors flooded the market, driving up prices and making home ownership increasingly difficult for first-time buyers.

Additionally, between 2005 and 2015, immigration outpaced housing supply, further exacerbating affordability issues. By the time these factors stabilised, house prices had more than doubled relative to incomes. Whereas the house price-to-income ratio stood at four times annual income in 1999, it has now ballooned to eight times income. In cities like Sydney, median house prices have soared beyond $1 million, when they should be closer to $500,000.

The Rise of a ‘New Class of Working Poor’

The consequences of this housing boom extend beyond financial concerns, fundamentally reshaping Australian society. Kohler points out that younger generations who cannot rely on parental wealth are effectively locked out of home ownership. Even those who do manage to buy a home face crushing mortgage burdens, leaving them with little disposable income. This has created a "new class of working poor"—individuals with decent jobs who struggle financially due to overwhelming housing costs.

A ‘Net-Zero Moment’ for Housing Reform

To resolve the crisis, Kohler suggests that Australia must establish a clear national goal—akin to the "net-zero" target in climate policy—to restore housing affordability. The objective should be to bring the house price-to-income ratio back to its pre-2000 level of four times income. Achieving this will require a balanced approach that addresses both supply and demand factors.

Tackling Supply and Demand Imbalances

Attempts to improve housing affordability have primarily focused on supply-side solutions, such as zoning reforms and medium-density development. However, Kohler and UNSW Business School Professor Richard Holden argue that tackling only one side of the equation is insufficient. Demand-side policies, such as tax reforms, are also necessary but politically sensitive due to past missteps.

One proposed solution is linking immigration policy directly to housing construction capacity. Kohler emphasises that rather than arbitrarily cutting immigration numbers—which can be controversial—Australia should ensure that increases in population align with housing supply growth.

Policy and Market Interventions

Kohler also highlights the significant influence of interest rates and financial regulation on housing prices. For instance, house prices fell in 2017 when the Australian Prudential Regulation Authority (APRA) tightened lending to investors. Similarly, prices dropped during the COVID-19 pandemic before rebounding due to record-low interest rates. Given this dynamic, policymakers must carefully calibrate economic levers to manage housing affordability without destabilising the financial system.

Furthermore, Kohler argues that rental market policies must shift to provide greater protections for tenants. While some state governments have introduced reforms to improve tenant rights, a more coordinated national approach is needed. Centralised planning—similar to the UK’s model—could help streamline zoning laws and ensure housing supply meets demand.

Conclusion

Australia’s housing crisis is the result of decades of policy distortions that have disproportionately benefited investors at the expense of first-time buyers. Addressing this issue will require bold, coordinated action to re balance the market. Kohler advocates for a national strategy that tackles both supply and demand factors while ensuring housing remains an accessible pathway to wealth for future generations. Without such intervention, Australia risks entrenching a permanent class divide based on home ownership.